Maya Varadaraj’s practice focuses on different issues regarding and surrounding women. Her graduate school thesis, was an artist awakening for her. Through the project she explored concepts of violence against women via social norms prescribed for them. Her practice continues to explore different avenues of discourse that are used to oppress women, and how they can be overcome. Maya’s naturally forthcoming nature allowed me to understanding the depth and research involved in her practice, and how multi-faceted her creativity can be.

1. What was your journey into art? Is this something you have always wanted to do?

You know honestly I always struggle answering this question, because hindsight is 20/20. Way back in High School I enjoyed chemistry but I also knew I would get bored because I wanted to do something creative. Not that chemistry isn’t creative, but I knew I wanted to do something with my hands. I didn’t think I would get into fine arts per se, so I went into design. I studied four years of fashion design, and even my masters degree is two years in this kind of off-shoot product design. While I studied design I got disillusioned with consumer culture. It just really bothered me, I felt like I could be doing more with my time. I could be giving back with my creativity. I wanted to that with design, but felt I wasn’t able to.When I started working on my thesis I felt that’s the closest I came to being able to give back, and express myself in a way that was honest. It sort of went from there. I’ve come to the conclusion that honest giving back to society will take time.

2. How do you feel you are giving back right now with your work?

I feel right now I’m just sort of in the process of articulating what I want to give back and my point of view. It’s a slow process, you don’t want to rush into things. Especially when you’re trying to figure out your point of view you should take time. Especially critiquing yourself and your own circumstances, which I do a little too often I think. I think that perhaps sharing my perspective and opening avenues of conversations that don’t seem sort of easy to have. I think that is helping in some way. I also think that for South Asians in the US, we are having very different conversations from what is happening in South Asia. I think bridging that communication, or having more similar conversation.

3. Did you grow up in the US?

No I grew up in India. I grew up in the South of India in a boarding school.

4. What do you think is one of the most difficult avenues of conversation that you have had through your work?

That’s a really good question. I don’t think I’ve come across any difficult conversations. I feel people have more or less been open to having the conversation that my work sort of provokes, people have been very good about that. I do think that there is a generational gap and misunderstanding. It’s very difficult to talk to older generations of women in India, or even here, about colourism or even sexual harassment. It’s always sort of like “well what did you do to provoke that?” Or “are you just being sensitive?”

5. So, I have a work of yours so could you tell me a little about that work and series?

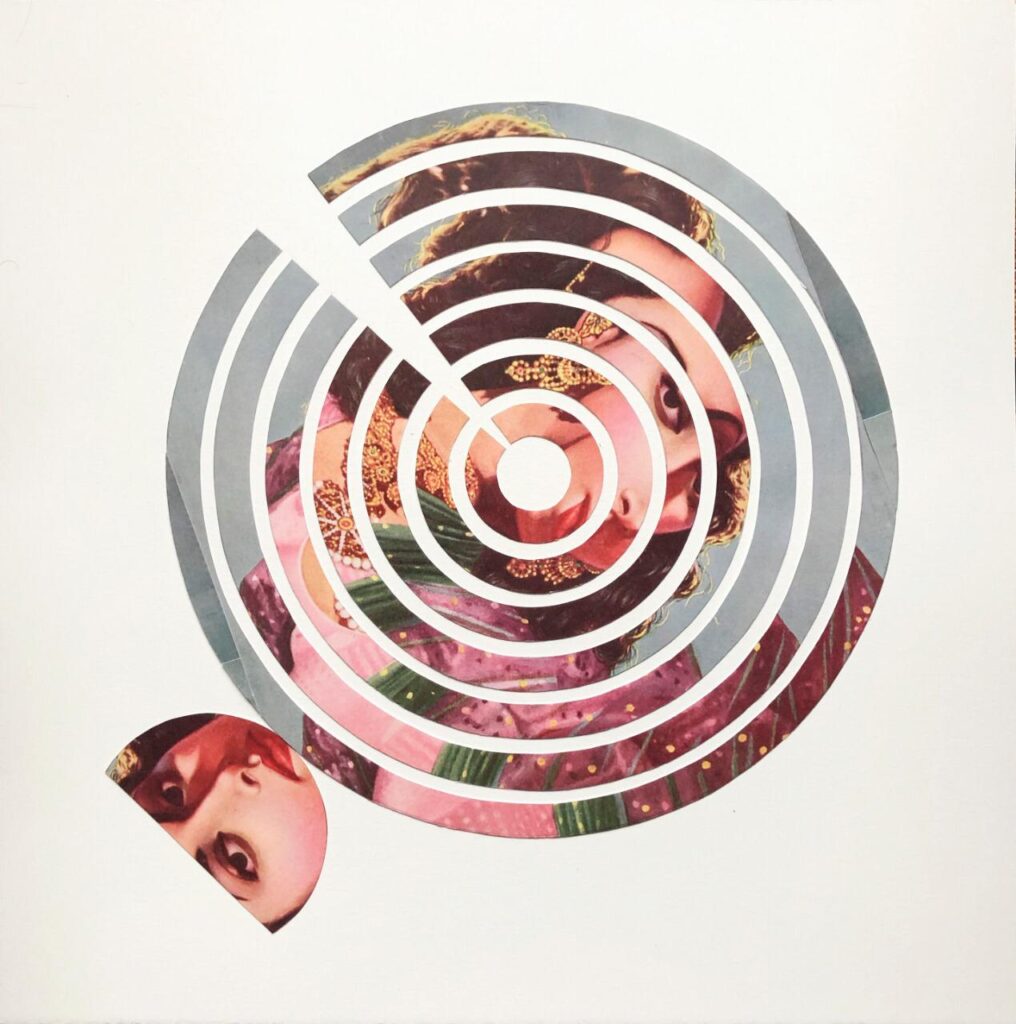

I named that series ‘Samsaram’. It’s a play on the words ‘samsara’, which means wife in Tamil, and ‘samskara’, which is circle of life and death, and rebirth. This series is me sort of evaluating a bunch of things. It’s me evaluating myself the way that I had responded to popular culture. In 2017 when I had combined the collages with water colour I was a little bit more critical of the kind of women portrayed in those illustrations. Subconsciously I felt maybe they weren’t doing enough or that they were blindly following prescribed behaviour and decorum of that time. But now having done more research into the political and social landscape of that time, I actually think those women were perhaps the more progressive women of that time. With this new series I feel I’m paying more attention to the gestures, and picking up on that and injecting humour into them, and combining them with the concentric circles to show introspection. It goes back to mandalas and concentric circles from Hinduism that tend to provoke meditation. So to elevate these women and grant them the kind of introspection that they deserve. At the same time I was, prior to working with these collages, I was drawing statistical drawings.

6. Would you then say you practice is very research oriented?

I would say sometimes I really have to pry myself from the research to get started on work. I frequently go back to it, especially when I face creative blocks. I go back to research to find my way back.

7. Was that always the case?

I would say perhaps I developed this behaviour, or developed this process in grad school, because my work was very research oriented.

8. So you’ve worked on a range projects, and you’re working on something new even now, but do you have something that you feel is an unrealised project. Unrealised because of budget, or COVID or something that you wanted to do but has not been able to happen. And if you had all the means in the world, you would drop everything and do that?

So Method Gallery had posted about this project last year called ‘Death and Taxes’, and I hit a massive roadblock with this project, because I wasn’t able to get the information I wanted. Understandably so, because people are very sensitive about death and taxes. So my objective with that was to take Benjamin Franklin’s statement, which is “there’s nothing certain, except death and taxes.” I’m paraphrasing, but that to me in the thought of consciousness was so provocative, because I think we as human beings are so certain about our high consciousness that this statement sort of undercuts that. I wanted to bring this objectivity to out consciousness and create this artist book of people who had died the last taxes that they paid, which is their funerary taxes and they only pay taxes on the products purchases as their funeral items. In my opinion that’s the last obligatory sakes tax. I actually went to a whole hunch of funeral homes, I tried to get an internship there. I really want to get these numbers, but everyone is so protective of them. Even though I said I don’t need names, just tell me the date of death and the amount of taxes paid. No one would give me that information. I even called IRS to see if they could give me that information, since the people were already deceased. I even sent a mass email to family and friends to ask if they could share that information.

9. How many people would you need information from?

I would say at least, I mean if it’s a book, 100-150. I actually had one girl whose family were in the funeral business, who said “Ok I can help you with this”, and then I stopped hearing from her.

10. So, would you do visual representation of this?

Each page was just 2 numbers, a date and a monetary amount. So it was going o be just that simple, but so impactful, because you look at that but you don’t know what you’re looking at.

11. That’s so minimalist and not something I would associate with you. It’s quite different from your other works. After this unrealised project do you have a favourite work or series of yours?

My thesis project is something I feel very strongly about. It’s the project that has given ideation to all my other projects, and it continues to serve as a research centre, because there’s just so much that went into it, and so many avenues of research under it that I can continue to go back to and explore. ore the relation between women and machines, that I had while working with those appliances?

12. What was your thesis project on?

So my thesis project was an installation that I made in 2017, where I was looking at the 2015 gang rape case of a woman in Uttar Pradesh who was a health care worker. The whole thing was video recorded and sent around the entire village and other parts of the country. She survived the rape, but I think her family disowned her when she told them. She also went to the local government and asked them to do something. They basically said this is your fault, because you solicited this attention. The thing is she was married and had a child. She had rejected this guy’s advances before and this caused a lot of anger within him. She was totally ostracised and ended up committing suicide. This is after the Nirbhaya case, so you would think that there would be a little more support, especially when the perpetrators are on camera and there’s clear evidence to what happened. Not that if there isn’t clear evidence and there isn’t that kind of clear information that women are not in the right, but in this case it’s an absolute no brainer.

It really bothered me, I found out that Uttar Pradesh has the highest rate of gang violence against women, and it is the largest manufacturer of glass bangles as well. I was like this is a really interesting correlation, and I started doing more research into the bangles that we wear. I always knew that breaking them was bad luck, or something taboo, but I didn’t know the extent of violence embedded in these objects and how it seeped into political language as well. That became my starting point from where I wanted to do something with these bangles.

I had enough research to show that they had become a symbol of inferiority and weakness. So I started with this act of deliberately breaking them, and I was looking for different ways of doing that. I wanted it to be a machine process, so I had a wet grinder at that time and I point them in the wet grinder and ground them up. I was like this worked really well, and I was like this is interesting because I’m using a home appliance, which is another area where women are subjugated often. So I rigged this process where there’s a wet grinder where the bangles are crushed up, its then transported by a vacuum cleaner into a mixing bowl, and then I found this microwavable kilt where you melt the glass in the microwave. So the whole process crushes and reforms glass bangles into Durga chakras, keeping it in the same cultural sphere. Because this was all happening in the domestic realm I continued my research in the two-dimensional visual propaganda and found these calendar illustrations to also dissect and modify, and that’s where all the work started.

13. So another question that I ask is do you have a favourite work (by another artist), or a work that inspires your practice?

So I came across Agnes Denes’ work last year, and I fell in love with it. It’s so inquiry based, and numbers based, and visually very intricate and result oriented. She basically created this massive wheat field in the downtown district of New York, which is crazy and amazing, because it’s basically this farm in the middle of this massive city. She’s just a genius, I love her work.

14. Do you have a favourite colour?

Right now it’s this yellow, ochre colour, but it changes.

15. And the last question, I ask everyone is do you have one work to describe your practice?

Critical.

Follow Maya Vardarj on instagram @maya_vara

You can reach out to her directly on email for any queries about her works at mvaradraj@saic.edu

Maya is currently showing at Sapar Contemporary. You can view the exhibition here